VIEW AND DOWNLOAD WORLD TENNIS GAZETTE VOL. 12 NO. 8

By JOHN MARTIN

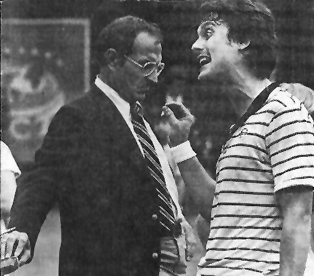

World Tennis Gazette/John Martin

MELBOURNE, Australia — When this year’s Australian Open ends on Sunday night (Feb 2), it will mark the completion of two weeks of largely flawless, argument-free work by more than 400 certified chair umpires and line judges.

In hundreds of hours of tennis combat at the highest level, the lone notable argument erupted between Australian Nick Kyrgios and Chair Umpire James Keothavong of Great Britain.

Losing a point to Rafael Nadal, Kyrgios smashed his racket and drew a stern glare and warning. Kyrgios glared back. The moment passed swiftly. There was no prolonged tantrum.

Keothavong prevailed, a Gold Badge Chair Umpire keeping the lid on a player noted for his temper.

Keothavong and his umpire colleagues hail from no fewer than 20 nations, including China, India, Kazakhstan, Germany, Croatia, Serbia, Sweden, Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal All had been trained and certified by national tennis authorities.

Each year in the world of international professional tennis, hundreds of men and women circle the globe to keep the scores and enforce the rules in a fair, impartial, and consistent manner.

It wasn’t always this way. Until about 45 years ago, tennis officiating was hit or miss.

Chair umpires were frequently buddies of tournament directors whose friendships with agents or players raised questions of unequal treatment.

Line callers were sometimes superb and sometimes drowsy. Rules were often subject to erratic revision on the run.

Players, meanwhile, competed in an air of uncertainty. In the mid-1970s, a small number of top male players repeatedly disrupted matches by outbursts aimed at distracting their opponents.

To be sure, many tournaments were graced with efficient, fair, and competent administration by skilled, experienced officials.

But many major tennis championships were sullied by incompetence.

With support slipping among fans and investors, professional tennis reached a crisis point.

In 1978, the Association of Tennis Professionals turned to an obscure savior: Dick Roberson of San Diego.

For much of 14 years beginning in 1972, Roberson worked quietly as a sales representative of Penn Racquet Sports. Each summer, he moonlighted as the supervisor of officials for the World Team Tennis circuit.

International Tennis Weekly, Oct 24, 1980

WTT’s organizers, working with Billy Jean King, directed Roberson to rethink the way tennis was conducted on the professional level.

He soon recruited experienced officials from the worlds of pro football, basketball, and baseball. Their task was to help him enforce a new style of tennis officiating.

“I said, ‘Here’s how we gotta cover the court,’ you know. So we got it down to a five-man system, and she (Billie Jean King) just absolutely loved it.”

Seeking reforms, he experimented, giving chair umpires authority to penalize and default players, no longer deferring to an off-court tournament referee.

“In the early ‘70’s,” Roberson said, “a few countries addressed the conduct issues with the U.S.T.A. being the leader in setting up some procedures that at least gave a warning to the player.

“But that procedure wasn’t used,” Roberson said, “because the chair umpires were afraid of the players.

“It was an old boy system,” he said. In Los Angeles at that time, he explained, a nod from the head tennis official of the city was the main qualification for an aspiring umpire to climb into the chair.

“You had to be one of his buddies in order to get in. I mean, they had no evaluation system.”

In search of innovation and reform, between 1978 and 1982, Roberson disappeared from his workplace in Southern California.

At the insistence of the ATP, which paid his yearly $35,000 salary, he was hired by the Men’s International Professional Tennis Council.

In effect, he was the world’s first paid professional tennis official.

Roberson’s mandate was to train and create a corps of paid professional chair umpires who would enforce the rules against profanity, racquet abuse, and disruptive behavior in the tantrum-filled age of Ilie Nastase, John McEnroe, and Jimmy Connors.

Tournaments “were losing sponsors,” Roberson said, “they were losing ticket holders, I mean, nobody wanted to sit courtside because of the vulgar language. I mean, it was dreadful.”

Roberson recruited referees and umpires to attend training schools he staged in Dallas, Paris, Sydney, and Hong Kong.

By 1980, the number of trained and certified Grand Prix officials topped 100, according to the Christian Science Monitor, which called them tennis’s “inspectors general.”.

Embarking on the ATP world circuit, Roberson hired three fellow supervisors, including Kurt Nielsen of Demark, the 1955 Wimbledon finalist.

Together they searched for men and women who would enforce a new code of conduct. In in the process, Rober-son persuaded the tennis establishments in the United States, Australia, England, and France to adopt his methods. Other nations followed.

One of his early recruits, Rich Kaufman, a linesman from the Pacific Northwest who lived in England, took instructions from Roberson, won his confidence, and was chosen to climb into the umpire’s chair in the 1983 Wimbledon Gentlemen’s Singles Final.

Kaufman later became Chief Umpire of the U.S. Open.

At an early meeting, Kaufmann recalled, his attention seemed to wander. Roberson took emphatic action.

“I was maybe sort of half listening, when he first started talking to me, and he grabbed my collar and pulled me in, ’Rich, do I have your attention?’ He was holding a sheet of paper. There were about 10 things on the sheet of paper. And I said, ’Yes, Dick. Yes sir.’

“And he kept holding my collar, not real tight, but tight enough to get my attention. And he went down the list of 8-9-10 things that he wanted me to concentrate on the next match. And after he said that, he said, ‘So, do you understand?’ And I said, ‘Yes Sir.’ He said, ‘Okay, you’re going on court next, do it right.’”

Brian Earley, who stepped down in 2018 from the U.S. Open position of Chief Referee, saw Roberson’s role in professionalizing the sport’s conduct as vital within a narrow universe of tennis officiating.

“He was known for his fairness, and also for sharing his ideas about the Code of Conduct with his colleagues, who then disseminated it to the referees and then the chair umpires. And he was also a big supporter of chair umpires. He understood that overrule was necessary,” Earley said in a 2011 interview with The New York Times.

The ability of chair umpires to overrule line callers was needed, so errors could be corrected. Roberson also pushed for uniformity, Earley said.

“He’s the one who said, ‘okay, let’s all do this the same way.’ There are many different fair ways to do it and you can decide what’s fair, but let’s all do it the same way.’”

”Dick Roberson was the true beginning of professional officiating,” said Phyllis “Woodie” Hoffman, 84, who served 46 years at the U.S Open starting as a line judge and retiring in 2014 as Chief Umpire.

“He was the best thing that ever happened here,” she told The New York Times.

Sixteen months ago at the 2018 U.S. Open, the concept of professional officiating faced its sternest test in many years.

In the women’s final, an angry Serena Williams and a duty-driven chair umpire, Carlos Ramos, engaged in a tense, bitter dispute.

Williams’ outburst, which included calling Ramos a “thief” and “liar” and repeatedly demanding an apology, was carried out in an angry tone that was audible to millions around the world.

Ultimately, it led to a series of match-ending exchanges that stunned the tennis universe as have few audible altercations.

The issue was Ramos’s discovery that Williams’s coach was signaling her from his courtside seat. Williams, who seemed unaware of the signals, erupted in indignation.

When she persisted, she collected penalty points under the established rules. Soon she was standing on a match-point cliff. It was too late to recover. Williams fell in defeat.

Condemnations flew. USTA President Katrina Adams criticized Ramos’s rigidity, then eased back in mild apology that managed to infuriate umpires and line judges. One veteran umpire exclaimed that Adams had thrown Ramos and his fellow rules keepers “under the bus.”

Roberson agreed. He also dismissed a parallel issue raised by Williams, who asked whether she and other women are held unfairly to a more rigorous standard than men.

A New York Times sports column at the height of the controversy was headlined “Serena Williams Picks the Wrong Time to Ask the Right Question.”

According to Roberson, women’s tennis adopted his same new standards in the 1970s regarding on-court misbehavior even though women were notably well behaved.

“Up to this time,” he wrote to World Tennis Gazette, “Women’s tennis did not have the same problem as the men. The Women’s Tennis Association did not have to address player conduct. There were no bad women.”

Some credit for today’s relative tranquility goes to the technology of Hawk-Eye’s instant replay cameras, which cut down on arguments which once entangled players and officials.

Roberson takes — and deserves — substantial credit for establishing a worldwide system of rules and certification for the men and women who call the lines and keep the scores.

From his retirement home in Phoenix, Roberson writes:

“This program is still going on today with some modifications in the training of court officials,” he said.

“Player behavior is under control and the integrity of the game back under control by properly trained tennis officials.”