VIEW AND DOWNLOAD WORLD TENNIS GAZETTE VOL. 13 NO. 3

By JOHN MARTIN

SAN DIEGO — He probably doesn’t know this, but Novak Djokovic owes his swift departure from the 2020 U.S. Open to an ex-sporting goods sales manager from Southern California.

The court discussion lasted perhaps 15 minutes between a chagrined and softly argumentative Djokovic and a determined and well-read US Open Tournament Referee Soeren Friemel.

The rule was the rule, Friemel said later, there was “no other option.” Striking anyone with a ball in anger or by accident calls for immediate default.

Dick Roberson, the man who rewrote the rulebook 40 years ago to ban “ball abuse,” watched the debate on television this month from his home in Phoenix.

“I put in ball abuse and racket abuse because that wasn’t in the code of conduct,” Roberson said, ”because I said that’s a temperament kind of thing, and you got to be careful with it because it can get dangerous.”

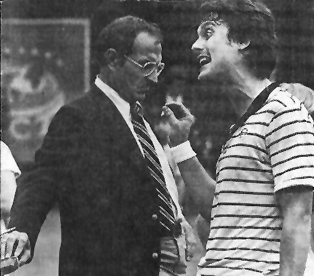

In 1978, Roberson was a Penn Racket Sports sales manager living in San Diego. Hired temporarily by World Team Tennis, he modernized the way officials enforced a streamlined rulebook he created.

Then he found himself recruited to perform the same task for players and tournaments across the world.

Caught in snatches of conversation on television, Djokovic seemed to be arguing with Referee Friemel that his seeding, ranking, and contrition toward Lineswoman Laura Clark deserved consideration in the decision to warn or default.

Should Djokovic have been given a warning? Four decades later, Roberson answered instantly:

“Oh, no. No, no. No, no, no, no. Hey, that was…when you hit a linesman or a ball boy…because he wasn’t even looking at where he was hitting it at…I think he was trying to get it back to the ball boy, but he missed, but he wasn’t even aware of where he was hitting it, and oh no, to me, that was an instant default.”

By the writer’s count and recount, that was seven consecutive “nos” followed by an eighth. No question, he said no warning was warranted.

Over the years, Roberson’s certainties and sensibilities earned him praise from all sides.

Phyllis Walker, the U.S.T.A.’s chief umpire, expressed it to The New York Times upon her retirement in 2014.

“Dick Roberson was the true beginning of professional tennis officiating,” she said. “He was the best thing that ever happened here.”

Roberson said he was pleased at how the U.S.T.A. had expanded the wording of his rule:

“I just had ball abuse and racket abuse in the code of conduct, and now they have it so spelled out, I mean, it’s like they made a dissertation out of it, and that’s good,” Roberson told World Tennis Gazette.