VIEW AND DOWNLOAD WORLD TENNIS GAZETTE VOL. 12 NO. 4

(This article is adapted from the writer’s story published by The New York Times on Sept. 8, 2013)

By JOHN MARTIN

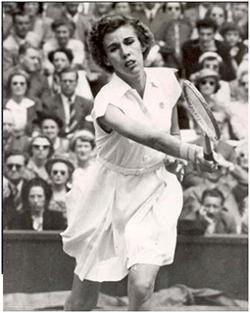

Maureen Connolly was not yet 19 when she won the United States women’s singles championship in 1953 at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, Queens.

With her 6-2, 6-4 victory over Doris Hart, Connolly became the second player after Don Budge in 1938 and the first woman to win the Australian, French, Wimbledon and United States championships in a calendar year. (Rod Laver in 1962 and 1969, Margaret Court in 1970 and Steffi Graf in 1988 followed.)

Connolly, a San Diego native known as Little Mo, stood 5 feet 4 inches and weighed 120 pounds. She captured nine consecutive Grand Slam events in which she participated starting in 1951, winning 50 straight matches while losing only one set.

Then Connolly’s leg was shattered in a horseback riding accident in 1954, ending her playing career when she was 19. She died15 years later. “It was the shortest of great careers,” said Bud Collins, a writer and historian, “but few got more done in many more years.”

In profiling the 40 greatest players from 1946 to 1996, Collins wrote of Connolly, “She may have been the finest of all female players.”

That view is not shared by those who argue that the strength, power rackets and serving speeds of today’s players would prevail.

“My serve has always been the major weakness in my game,” Connolly acknowledged in her 1954 book, “Championship Tennis.” Switched from left-hander to right-hander by an early coach, she was working with Les Stoefen, a 1930s doubles champion, striving to hit “a hard flat ball and a good reliable spin,” she said.

Ben Press, 89, a San Diego teaching professional and one of Connolly’s closest friends, said, “Her serve was weak by comparison with today’s girls, but the other girls would have just as hard a time holding serve.”

Connolly once faced Pancho Gonzalez, the world’s top men’s player in the 1950s, in a mixed doubles exhibition on a hardwood tennis court in San Diego. Connolly insisted Gonzalez “not hold back,” Press said.

“When Pancho served — which was the best serve in the world at that time — on the boards,” Press said, Connolly “handled Pancho’s serve a majority of the time.”

Tony Trabert, who won five Grand Slam titles in the 1950s, praised Connolly’s skills and competitive instincts but questioned her ability to prevail today.

“I think these girls would overpower her,” he said in a telephone interview. “They’d jump all over her serve. I think of a Serena Williams or someone like that.”

Even so, Trabert, 83, said Connolly, like champions from other eras, deserved respect and admiration.

“Do me a favor,” he said. “Speak very favorably of Maureen Connolly, because I think she was a terrific champion. She was a terrific lady and did a wonderful job.”

Trabert spent 31 years as the lead CBS Sports tennis analyst at the United States Open, beginning in 1971.

“Who can say who would have beaten whom?” he said. “I think giving them a level playing field, let them be the same age, fit, and the same kind of equipment, and in many cases, the top player of any era would have adjusted and done very nicely.”

One Connolly trait shared by top players today is a fierce hostility on the court, said Steve Flink, a tennis analyst and historian.

In “Forehand Drive,” her 1957 autobiography, Connolly wrote: “I hated my opponents. This was no passing dislike, but a powerful and consuming hate. I believed I could not win without hatred.”

Emphasizing that he was speaking of Williams’s behavior on the court, Flink said: “I think Serena definitely has it. I think the others do too, the Navratilovas, the Grafs, the Everts, Billie Jean. That’s while they’re out there. Nothing is going to get in their way. Nothing’s going to stop them.”

Angela Buxton, an Englishwoman who reached the Wimbledon final in 1956, was beaten by Connolly in the 1954 French Championships quarterfinals.

“She was ice, all I can tell you, ice,” Buxton, 79, said. “She’d strut backwards and forwards from the right court to the left.”

After the 1953 United States women’s final, Allison Danzig wrote in The New York Times that the match between Connolly and Hart had been fierce.

“Miss Hart, a finalist five times and a strong hitter in her own right,” Danzig wrote, “resorted to every device, including changes of spin, length and pace, in an effort to slow down her opponent.”

Hart, 88, laughed as she recalled the match.

“She aimed for the lines, and she hit them most of the time,” Hart said of Connolly, adding: “She just exuded confidence, you know. Everybody felt it. No matter what the score was, you felt like she was always ahead.”

In 1953, Hart showed determination in defeating Connolly in the final of the Italian Championships, 4-6, 9-7, 6-3.

Then, at Wimbledon, Connolly defeated Hart, 8-6, 7-5, in the final, a match praised by Flink in his 2012 book, “The Greatest Tennis Matches of All Time.”

“When I came off the court, I felt like I had won,” Hart said. “I couldn’t play any better. I felt that, deep down. She was better in every way.

“I always thought that. Her record, they never mention it today. Never. She won everything by the age of 19.”

This year, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp honoring “Lil Mo.” On Oct. 20, the Balboa Tennis Club and the Greater San Diego City Tennis Council will honor Connolly and Press in a special tribute, including the dedication of a Press Family Tennis Pavilion for tournament play.