VIEW AND DOWNLOAD WORLD TENNIS GAZETTE VOL. 11 NO. 3

By JOHN MARTIN

March 2019

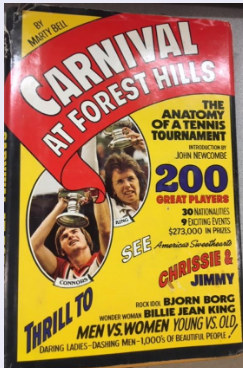

Carnival at Forest Hills book cover

Tennis books come in many sizes and shapes, but Carnival at Forest Hills, Marty Bell’’s book-length account of the 1974 United States Open breaks new ground.

Bell was executive editor of Sport Magazine who migrated to Broadway, where he produced shows, then moved to Washington, where he took a sharp turn to become a public policy consultant on health issues.

Attempts to contact him failed. A New York friend who wrote a book with Bell’s help a decade or more ago said they drifted out of touch after he moved to Washington.

Attempts are underway to find five people he thanks for sharing the reporting tasks he undertook to write Carnival. The book’s cover carries a tennis racket bag’s worth of catchy phrases, the kind a carnival barker might use to attract an audience: “THE ANATOMY OF A TENNIS TOURNAMENT,” “200 GREAT PLAYERS,” “30 NATIONALITIES, 9 EXCITING EVENTS.”

It feasts on personalities, begging readers to watch “America’s Sweethearts: CHRISSIE & JIMMY,” “THRILL TO Rock Idol BJORN BORG, Wonder Woman BILLIE JEAN KING.”

In a final burst of exuberance, the cover promises that any reader who ventured into the book’s 192 pages would meet ” DARING LADIES, DASHING MEN, and 1,000’s of BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE!”

Book endorsements (blurbs by fellow authors) are notoriously and suspiciously positive, but the three tennis figures who grace Carnival’s back cover sound sincere.

Cliff Drysdale is direct: “The Forest Hills carnival is stripped of its merry-go-round trimmings and you are left with insights into the raw, often surprising emotions of players and spectators.”

“I was delighted,” said the player-turned-broadcaster, “to get a new, interesting and comprehensive look at the game that’s been my.life.”

Author and analyst Bud Collins calls Carnival “absorbing,” not especially encouraging.

But Frank Deford of Sports Illustrated positively gushes — or so it seemed. He calls Carnival “the most complete story ever told of one tennis tournament–a Wimbledon of a job on Forest Hills.”

Since few other book-length accounts exist of a single tournament, the praise may be faint. So what awaits a casual reader 45 years after Marty Bell sat down and put it on paper? Celebration of a beloved sport.

Forest Hills means the West Side Tennis Club, of course, founded in 1892 by 13 players who rented land along the west side of Central Park in Manhattan and moved to Queens in 1912. By the 1970s, Americans were the world’s best professional tennis players, but Forest Hills was on its last legs as the host of the U.S. Championships.

“It is easy to criticize Forest Hills,” observed John Newcombe “The conditions are often comparable to playing the Super Bowl in a high school stadium.”

Author Bell sets the stage by placing the aging club at the center of a vast phenomenon outside its control.

“By 1974,” he writes, “34 million Americans were playing the game (up from 10 million in 1970) and the professional men and women stars were making almost $300,000 a year. The game had become big business.”

And Bell had become interested in the gritty details that fascinate readers who play the game or love watching it from their seats.

Here is Bell’s description of the first moment of play:

“At twelve minutes past noon, on a grass tennis court surrounded by a gray cement stadium, John Newcombe, an Australian wearing a pink shirt and an exaggerated walrus mustache, tossed a yellow ball in the air, smoothly swung his steel racket down behind his back and then up over his head until it struck the ball and sent it flying over the net. Waiting on the other side was Ramiro Benavides, a small Bolivian, dressed unobtrusively in white but wearing a colorfully printed headband to keep his long brown hair in place. As the ball bounced up to him, he swung his wood racket and directed the ball back across the net and past Newcomb, who had run to the barrier of rope rectangles that separated the two. The ball bounced a few feet inside of the base line and Benavides let the faintest smile show on his face. The U.S. Open had begun. And he had won the first point.“

Five days later, as play proceeds, Bell makes an assessment of Billie Jean King and the rising strength and status of women’s tennis. All the usual suspects (rising stars all) are mentioned: King, Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, Margaret Court, Virgina Wade, and others.

Bell, himself a tennis player, adds a mildly comical portrait of Julie Heldman, a pioneer, with King, as a player and daughter of the founder and publisher of World Tennis, the highly regarded magazine.

“‘Junkball Julie’ they call her. She dinks. She lobs. She’ll even hit the ball off the handle to frustrate an opponent. She plays tennis the way a trick shot artist plays golf. No power in her game. Just personality. That’s right..”

Despite Heldman’s quirkiness, Bell reports, she possesses an iron will. After a night suffering from poisonous clams, she upsets Navratilova, 6-4, 6-4, to move into the quarterfinals at Forest Hills.

Carnival delivers such nuggets from deep within the draws. Bell and his five colleagues are good reporters. Unknown at the time, the tournament had only a few years left at Forest Hills.

Despite a series of remarkable sketches, perhaps the most striking observation in Carnival comes not from Bell and his team of reporters but from the Australian, John Newcombe, who won in 1973.

Forty-five years later, with few American men players in the top ranks, it is startling to read his assessment: “Wimbledon is kind of a special event now. It is like the Masters in golf. It is a two-week celebration of which the actual tennis is only a part. But the U.S. Open is the closest thing we have in tennis to a world championship.”

Newcombe adds: “The United States has taken over tennis now and made it its own game.”

In money terms, this might still be the case. These days, Flushing Meadows invariably comes up with the most prize money but except for the dominance of Venus and Serena Williams, American players began fading shortly after the turn of this century.

No American has won the men’s title since Pete Sampras (2002) and Andy Roddick (2003). In the 45 years since Carnival, Americans won the men’s title 12 times.

Reading an unusual book like Carnival at Forest Hills puts things in perspective. So, for the record, who won the titles at the carnival in 1974? Jimmy Connors defeated Ken Rosewall, 6-1, 6-0, 6-1, and Billie Jean King defeated Evonne Goolagong, 3-8, 6-3, 7-5.

Bell salutes Shakespeare. Perhaps he rests here best: Shakespeare joins the Carnival staff from The Tempest.

“Be cheerful, sir,” says the Bard,

“Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind.”