Naomi Osaka, Meet Maureen Connelly

VIEW AND DOWNLOAD WORLD TENNIS GAZETTE VOL. 14 NO. 2

By JOHN MARTIN

FLUSHING MEADOWS, NY (VIA SAN DIEGO)— Grand slam tennis seems to be examining itself closely these days. So after two weeks of photographing dozens of players and a coach raising their fists on my TV screen in this year’s U.S. Open, I decided to look closer.

Buried in the rulebook, I’m told, are warnings to professional players not to shake their fists in each other’s faces. A threatening motion delivered at close range deserves at least a point penalty or a chair umpire’s warning, according to a retired chair umpire I consulted.

But delivered from 30 feet away on the other side of the net, facing your coach as he or she raises a fist and scowls, your gesture will likely be ignored.

To be truthful, part of my curiosity flows from the way these raised fists come with facial expressions that look like deep anger or full-blown rage.

The most extreme example was the combination grimace and scowl on the face of Matteo Berrettini of Italy at the end of a point in one of his early matches in this year’s U.S. Open.

In a later round, Novak Djokovic seemed to be screaming from the depths of his soul. The same clenched fist appeared with less dramatic expressions of rage from many other players.

Almost nobody talks about this, at least in public. A digital search of 176 interview transcripts provided journalists covering the 2021 U.S. Open found only one person mentioned the word “fist.”

Jorge Fernandez, father of women’s finalist Leylah Fernandez of Canada, used the term “fist pump” to describe the smiling gesture his daughter often makes while summoning the crowd’s support. He remembered watching her win a 16-and-under national championship as a 12-year-old.

“I remember just watching her coming to the net, volleying, right? She would just turn around and little fist pump, just walk away like as if it’s something completely normal, like she’s been doing it for many, many years,” he told reporters. “I think that poise has come from her watching a lot of tennis, watching some of the big names.”

Grand Slam tennis deserves greater scrutiny because of Naomi Osaka’s struggles with emotions and her effort to deal with depression and anxiety.

After writing a Time Magazine cover essay (“It’s O.K. TO NOT BE O.K.”) Osaka encountered reporters at this year’s U.S. Open. When she steps on court for a match, she was asked, can she block out all distractions?

Osaka understood the concept: “So it would be really cool if I could, like, draw that line and be able to be like a robot Superman that could go on the court, focus just on tennis. But, no, I’m the type that kind of focuses on everything at one time. That’s why, like, everything is sort of muddled to me.”

Several days later, the distractions took their toll. Osaka lost in a third-round upset, 5-7, 7-6, 6-4, to the talented Ms Fernandez. Here’s how Osaka described what happened, answering a reporter who asked about her tantrum on court:

Reporter: “Usually you’re very composed. Tonight there were racquets thrown, shows of emotion. What do you think that was coming from?”

OSAKA: “Yeah, I’m really sorry about that. I’m not really sure why. Like, I felt like I was pretty — I was telling myself to be calm, but I feel like maybe there was a boiling point. Like normally I feel like I like challenges. But recently I feel very anxious when things don’t go my way, and I feel like you can feel that. I’m not really sure why it happens the way it happens now.”

As the press conference was ending, she added: “I honestly don’t know when I’m going to play my next tennis match (tearing up). Sorry.”

“I think I’m going to take a break from playing for a while.”

Many players seem regard their raised fists as a silent expression of pain or anger.

Italy’s Berrettini quoted Djokovic as using the term “good anger” as a way to win matches.

Great Britain’s Emma Raducanu and Russia’s Daniil Medvedev, the new U.S. Open Champions, raised their fists too, but sparingly.

Canada’s Fernandez used her smile and fist to stir fan support. She reserved her serious expression and fist for her opponents. Belarussian Aryna Sabalenka returned the favor.

How did all this get started? I’m not certain but I have a modest theory.

Naomi Osaka, take a deep breath. Meet Maureen Connolly.

In 1953, she became the second person after the immortal Don Budge (and first woman) to win a grand slam, the four most important international tennis championships in a single year.

To most everyone’s surprise, Connolly carried a silent weapon for every opponent she faced: hatred.

The San Diego teenager admitted in her 1957 autobiography, Forehand Drive:

“I hated my opponents. This was no passing dislike, but a powerful and consuming hate. I believed I could not win without hatred.”

Many opponents felt Connolly’s wrath. But in a surprising assessment, Doris Hart, who lost to Connolly, 8-6, 7-5, in an epic 1953 Wimbledon final, saw her foe not as hateful but supremely determined.

“She aimed for the lines, and she hit them most of the time,” Hart said: “She just exuded confidence, you know. Everybody felt it. No matter what the score was, you felt like she was always ahead.”

A few years ago, the U.S. Postal Service honored Connolly, crowning an artist’s sketch of her with the phrase “Little Mo.” the words a sportswriter chose as her nickname. Despite her size, 5 feet, 4 inches, 120 pounds, she was seen as possessed of the kind of firepower associated with a well-known warship of the day, the USS Missouri.

Osaka appears to see her personal dilemma as a lack of confidence. The New York Post quoted a recent Osaka tweet in which she opened up about her mental health.

“She is trying to change her ‘extremely self-deprecating’ view of herself,” according to Post writer Zach Braziller: “The two-time U.S. Open champion wrote that she’s spent a lot of time reflecting on herself.” He quoted her confession:

“Recently I’ve been asking myself why do I feel the way I do and I realize one of the reasons is because internally I think I’m never good enough.”

At 23, Osaka became the world’s third-ranked women’s tennis player, earning more than $50 million, yet she remains deeply worried.

“I never tell myself that I’ve done a good job but I do know I constantly tell myself that I suck or I could do better.”

Is there a lesson here? For me, yes. In the 1950s, competing as a 16-year-old in the National Public Parks Junior Championship played in Los Angeles, I decided to try an experiment: Before, during, and after every match, I would not talk to my opponent.

When I won my first-round match by default, I joked to myself that my theory was working.

But then I won my second-round match, moving in sullen silence, avoiding eye contact, looking elsewhere.

I did not hate my opponents. But, like Osaka, I felt I was not very good. I was desperate to find a way to focus completely on my shots. I didn’t care if my silence came across as hostility.

My next opponent, in the Round of 16, had no problem with my silence or my strokes. He rolled over me 6-2, 6-1.

I was devastated. I had misjudged the power of a scowl. If there was a lesson for me, it was: Raise your game, not your fist.

In August, just days before the opening rounds of this year’s U.S. Open, a New York Times headline advised readers to “Channel All That Rage Into Your Workout.”

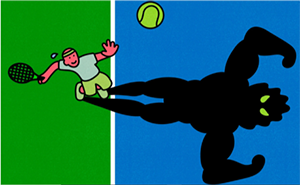

New York Times. A California newspaper headlined the story and this sketch: “The Rage Workout.”

A sketch accompanying the story showed a cartoon tennis player tossing his serve into the air while a shadow monster grew out of his body, its face locked in anger, suggesting internal rage.

Artist Gabriel Alcala was illustrating a little-noticed trait among athletes and others. The Times writer Erik Vance asked several questions, including Is “slamming a tennis ball across the court good for the mind?”

But whose mind? Why would a coach raise a fist from his or her box seat? What does the fist say to a player changing ends?

Five years ago, Allen Fox, who easily defeated me in a 1950s junior tournament before embarking on a career as a top player, coach, and sports psychologist, explained the pressures of tennis to Sports Illustrated writer Tim Newcomb.

“Dealing with…pressure while on the court in a virtual island of your own thoughts requires mental training as much as physical training,” Newcomb concluded.

“The best coaches are all very good psychologists,” Fox said. “That is most of their job, controlling the player’s emotions. The game is extremely stressful. You can’t relax for a second and so that’s very difficult to maintain.”

Maintaining elite play requires mental care. “What the players are doing out there, most of the time between points, is basically controlling their emotions,” Fox said. The SI article is titled “How mental coaching helps the pros manage emotions.”

Watching the world’s top player smash his racket on Arthur Ashe Stadium Court offered me another way to interpret what 2021 top seed Djokovic had in mind when he answered announcer Darren Cahill’s question, “What’s going through your mind?”

Djokovic was about to step on court and seek his 21st grand slam championship, the all-time highest number for a male player.

Djokovic said: “You don’t want to know.”

Hmmm. Novak Djokovic, meet Maureen Connolly. I think she knows.