VIEW AND DOWNLOAD WORLD TENNIS GAZETTE VOL. 14 NO. 1

By JOHN MARTIN

MELBOURNE (VIA SAN DIEGO) — Each year, in the days before play begins, the Australian Open stages a remarkable stunt.

It assembles all its ball kids (a record 394 this year) in a public space (often the Victoria Parliament steps). Then it asks them to simultaneously thrust a tennis ball into the air

Press photographers snap furiously. Within minutes, their images circle the globe to say the Australian Open is about to begin.

Nearly 15 years ago, the sight of this event in Melbourne (see photo, Page 3) led me to consider the often overlooked roles ball kids play in the sport.

“Ball kids serve as a link to a simpler time,” I wrote, “when tennis’s virtues were more widely seen as good sportsmanship, fair play, hard work.”

“Today, ball kids across the globe remain mostly young and impressionable, eager to please, often uncertain of their status, and everywhere prized for their service.”

What they do hasn’t changed much. But what tournament officials do to celebrate the events they serve has jumped into new realms.

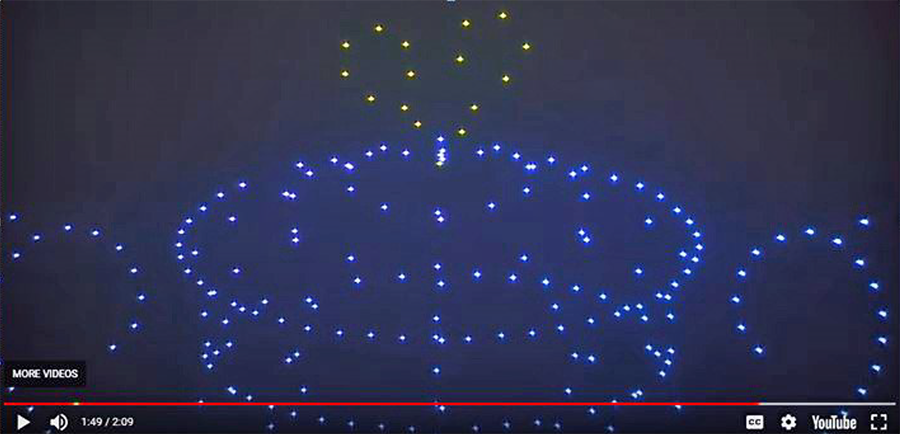

This year in Melbourne, AO officials staged a 12-minute nighttime drone show. They called it a “fun mix of retro depictions of the sport.”

The drones were launched from Olympic Park, the images forming and vanishing in the night sky. A huge tennis ball appeared, a championship trophy spread its outline across hundreds of feet of blackness, the shape of a tennis court emerged across hundreds of feet of inky sky.

Some years ago, when the first shots started spraying the courts in Melbourne, a tanned, white-haired man switched on his television set and peered back in time.

Chris-Crabbe was a 13-year-old ball boy for the 1946 Davis Cup match between Australia and the United States, the first played after World War II.

Jack Kramer and Ted Schroeder won the cup, 5-0, to return it to the United States.

But it was their American teammate, Frankie Parker, who left an indelible impression.

“Parker was the only bad-tempered one, even hitting a ball at one of us, for some offense,” Wallace-Crabbe told me in an interview for World Tennis Gazette.

Within a decade, the young Australian began forging a career as a university professor that included stints at Harvard and Yale. Ultimately, he became one of Australia’s foremost poets.

This year, like their 1946 predecessors, these young workers faced the possibility of bad tempers. But unlike Wallace-Crabbe and his teammates, who mostly wore white, they now wear the tennis equivalent of a sandwich board.

In 2012, their caps, shirts, and shorts bore an alligator image made famous by the 1920s French tennis champion Rene Lacoste. Today, Ralph Lauren’s familiar polo player rides herd.

Still, the lessons ball kids learned in 2012 remained remarkably similar to those taught their 1946 predecessors: Teamwork, timing, and self-control.

“I suppose I learned discipline,” Wallace-Crabbe said. “It was all quite tense, having to throw the ball with one bounce to the player’s dominant hand, and then scurry fast across the court itself.”, a Melbourne schoolyard.

But there, perhaps, the similarities end.

In 1946, the future poet and his teammates were recruited from Scotch College, located across a narrow creek from the Kooyong Tennis Club, where the Davis Cup matches were held.

By 2008, the search for Australian Open ball kids stretched across oceans. Recruiters staged tryouts in South Korea, India, and Singapore as well as the Australian continent. The team hired 337 ball kids from 1,400 applicants.

The four grandest slams all have stories to tell.

Wimbledon’s ball boys were once recruited from orphanages. At the French Open some years, the ball kids begin each day marching across the grounds of Roland Garros and chanting in French:

“We are the ball kids,

“We are the best in the world,

“We are ready to help the players.”

An Australian Poet Weaves Thoughts of Tennis Into an Ode

As far as I know, Wallace-Crabbe has never written an Ode to the Ball Kids.

He’s not commenting at present but it’s not out of the realm of possibility that if he saw the Australian drone stunt this year, he might be drafting a sonnet for tennis drones.

Images of tennis appear in many of his poems, describing a love of the sport kindled partly by his experience as a ballboy in 1946 and his delight in playing the sport for many years.

In “My Ghost,” he explored the images swirling in the minds of his friends.

— JM

My Ghost (Excerpt)

By Chris Wallace-Crabbe“…They just might glimpse my feathery shade

“playing what he has always played,

“ghostly tennis

hour after hour.

“Whom does he play against?

“And by what power?

How a TV Comedy Satirized U.S. Open ‘Ball Man Experiment’

In 1993, Television Comedian Jerry Seinfeld satirized the U.S. Open’s use of adult ball kids.

Viewers saw Kramer, Seinfeld’s clumsy neighbor, attend a tryout and win a place among U.S. Open ball persons, only to dash onto center court and knock over Monica Seles in the women’s final.

In the stands, Seinfeld remarks: “Thus ends the great ball man experiment.”

In real life, the “experiment” continued.

“I will not knock anyone over,” insisted Maria Diegnan, 47. She was a Florida housewife and mother of four who served at the 2007 U.S. Open, enduring a 19-hour bus trip to attend her first tryout and win a place at Flushing Meadows.

She said her brother teased her about the possibility of repeating Kramer’s blunder.

She was not worried:

“No, not at all,” she said, with a broad smile. Grew out of a longstanding insistence that age should not be a barrier.